/

Small Country, Big Deep Tech Nation: Switzerland as Europe’s Technology Hub

Original article by Eugen Albisser for Technik und Wissen, published December 8, 2025

While the world talks about GenAI, Switzerland is quietly building something almost as significant: an industry founded on physics, precision, and patience. Deep tech—the fusion of science and entrepreneurship—is becoming the heart of the next economic era here.

Anyone walking through ETH’s laboratories these days can smell ozone and machine oil, hear the hum of refrigerators full of cell cultures, and see young doctoral students who aren’t just tinkering with apps, but building robots that will later operate in mines or filter CO₂ from the air. An industry is emerging here—slowly, but with tectonic force. Switzerland is becoming a global deep tech nation. Not through overblown startup hype or pitch events, but through quiet, scientific precision.

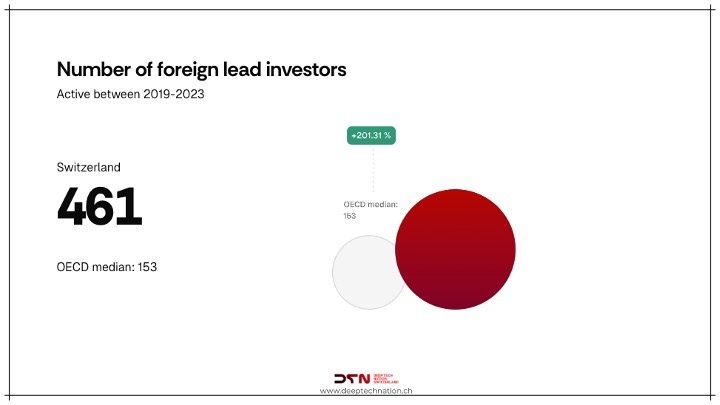

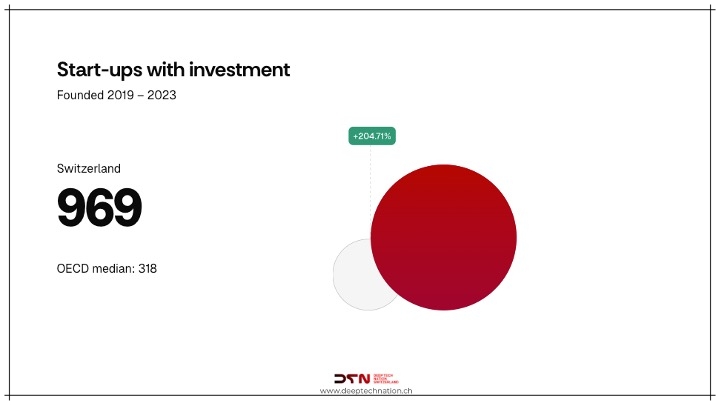

According to the Swiss Deep Tech Report 2025, 60% of all venture capital in Switzerland now flows into deep tech companies—more than in any other country in the world. Per capita, Switzerland ranks third behind the USA and Israel. And it attracts investors from around the globe: over 85% of capital now comes from abroad. A weakness? Perhaps. But also a compliment: the world believes in Swiss engineering.

The Two Machines That Produce Innovation

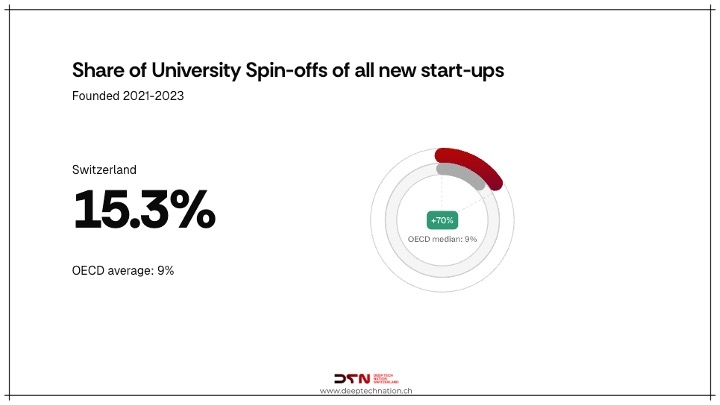

The backbone of this development are two institutions that have few equals worldwide: ETH Zurich and EPFL Lausanne. Together, they rank among the five leading European universities in terms of the economic value creation of their spin-offs. Add to this research institutions like CSEM, PSI, or CERN—a network of inexhaustible knowledge.

The ETH/EPFL axis forms the backbone of a so-called “Alpine Tech Cluster” connecting Zurich, Lausanne, Basel, and Geneva, extending across borders to Munich, Milan, and Grenoble. This cluster now ranks among the two most productive deep tech centers in Europe. Here, startups are emerging that fuse biotech, robotics, semiconductors, and AI. It’s a mix that reaches deep into the engine room of industry.

Deep Tech: The Slow Kind of Innovation

Deep tech is not the impatient sibling of the traditional software industry. On the contrary: it demands patience. Its products don’t emerge from app ideas, but from materials science, quantum experiments, or robotics research. It takes years before it’s ready for market, but in return, it creates foundations that endure for decades.

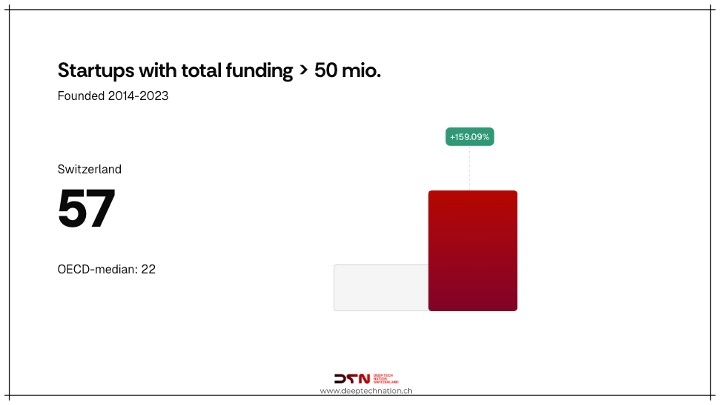

Switzerland has developed its own model from this: first years in the lab, then slow growth, and only when the technology is stable does the big money come. This happened with AutoForm (sheet metal simulation software), Duagon (computer technology for railways and industry), or ExcellGene (bioproduction for pharma). Private equity firms like Carlyle, Astorg, or Archimed bought in late, professionalized the structures, and later sold for hundreds of millions of dollars.

This pattern runs through many Swiss success stories: Navori Labs in digital signage, Spineart in medical technology, NetGuardians in cybersecurity, Nexthink in digital employee experience, and SonarSource in software code quality. Swiss deep tech companies grow quietly but robustly. They build real machines, real materials, real jobs.

The New Mix

Just ten years ago, deep tech in Switzerland was almost exclusively synonymous with biotech. But the picture has changed radically. According to the report, around 23% of new deep tech companies since 2021 have been founded in the AI/Machine Learning sector—twice as many as before. Alongside this, sectors like robotics, TechBio, Climate & Energy, or Semiconductors & Quantum are growing particularly fast.

Companies like ANYbotics (autonomous robots for industrial inspections), Ecorobotix (AI-controlled precision agriculture), Lakera (AI security platforms), Scandit (data capture), Distalmotion (surgical robots), or Climeworks (CO₂ capture from the air) show that deep tech is no longer just an academic phenomenon. They exemplify both the transition from research to global industry and a Switzerland that is realigning its strengths.

Light and Shadow

Yet the rise has a blind spot that could become dangerous: capital. While Swiss funds and support programs cover the early phase—roughly a third of seed and Series A rounds—96% of late-stage financing comes from abroad, specifically from the USA.

For Switzerland to remain the owner of its innovations, stronger engagement from domestic capital is required. Institutional investors in particular, such as domestic pension funds, could play a key role by investing a portion of their assets in the late growth rounds of these forward-looking Swiss technology companies. This would not only open up high return opportunities but also permanently anchor value creation and jobs in Switzerland.

If Switzerland wants to keep its deep tech companies here, it needs a stronger domestic backbone: funds that can invest 50 million, not just five. Otherwise, the story ends like many biotech companies: invented in Zurich, sold to Boston or Beijing.

Action is also needed on talent. Zurich today has the highest density of AI specialists in Europe: 3.5 core AI talents per 10,000 inhabitants—more than twice as many as Germany or France. But competition from London, Tel Aviv, or San Francisco never sleeps. And then there’s a typically Swiss weakness: cultural risk aversion. Too many projects still fail due to insufficient courage, not insufficient technology.

And Now?

Switzerland stands at a crossroads. It can view deep tech as a scientific export good, or as an industrial opportunity to reinvent its own economy. The fact is: the raw material is here. The research is here. The capital too, if you know how to get it.

Perhaps this is the real “Swiss Way” in the 21st century: no revolution, but a precisely engineered, scientifically grounded transformation of industry. Screw by screw, algorithm by algorithm. The only question is: will Switzerland remain the owner of this revolution, or merely its workshop?

“We Cannot Just Be the Inventors”

Interview with Joanne Sieber, CEO Deep Tech Nation Switzerland, on risk aversion, the lack of large funds, and the consequences for Switzerland as a deep tech hub.

Joanne Sieber, your report shows: 96% of late-stage financing (Series B+) comes from abroad, while Swiss investors are primarily active in the early phase. What are the structural reasons for this?

That’s the core question. First of all: it’s not about regulatory hurdles. The BVV 2 reform of 2022 gave our pension funds the opportunity to invest up to five percent of their capital in venture capital. Nevertheless, actual investments are currently still below one percent.

The underlying problem is that this asset class is still relatively unknown to institutional investors. Added to this is a so-called “chicken and egg” problem. The Swiss VC ecosystem, with an average founding year of 2016, is still relatively young. Actual returns are only realized after about twelve years, and reputation is only built after the second fund. This leads to institutional investors being hesitant because there’s often no sufficient track record yet.

Are there other obstacles?

Yes, because another obstacle is the structure of the Swiss VC landscape. There are many small funds here whose size is often not attractive enough for pension funds. Pension funds cannot take on too much exposure in a single investment. If only a small amount can be invested due to fund size, the effort for an investment often doesn’t pay off.

Additionally, internal know-how and experience in venture capital investments in the pension fund sector is still limited. The resources to professionally evaluate private market investments are often lacking. That’s also why we want to establish the AWI Deep Tech Fund as an investment vehicle that offers pension funds a simple way to invest in deep tech growth-stage startups and achieve attractive risk-adjusted returns. We’re talking to many pension funds about this and offering educational programs to introduce them to this asset class.

“We Definitely Need More Institutional Capital”

What would need to change specifically so that Swiss funds can invest 50 to 100 million francs in deep tech scale-ups?

We definitely need more institutional capital. Only then will we get the larger tickets needed to finance the growth stage—although 100 million single investments will still remain exceptions here. The AWI Deep Tech Fund is a step in this direction.

When we look at our European neighbors, we see that the EU has recognized that the growth problem cannot be solved by the market alone: it needs government support and guarantees to correct market failure. A public-private approach, like the EU Growth Fund, where a portion comes from the EIB and the majority from European investors, would also be desirable in Switzerland.

Switzerland invests a lot of money in education, research, and development. That remains important, as it forms an essential foundation for innovation and thus for startups and scale-ups. But then, when Swiss business and society would really benefit from the growth of such emerging companies—through new jobs, tax revenues, etc.—we leave the field to others. We should rethink this. Especially in today’s time of changing power dynamics, no country can afford this anymore.

“For some of our technologically successful startups, going abroad or selling is often the only way to obtain the necessary growth capital.”

“The Fact That 96% of Late-Stage Deep Tech Financing Comes from Abroad Speaks Volumes”

Can you give examples of Swiss deep tech companies that were sold or moved abroad due to lack of capital—even though they were technologically successful and could have stayed in Switzerland?

I can’t give you specific names here, but the fact that 96% of late-stage financing in deep tech comes from abroad speaks volumes. International scaling is obviously essential for the deep tech sector, as the Swiss domestic market is too small. For some of our technologically successful startups, going abroad or selling is often the only way to obtain the necessary growth capital. We must strengthen our own financing system so that we remain not just the inventors, but also the owners and beneficiaries of deep tech opportunities.

According to the report, Zurich has the highest density of AI talent in Europe. How many of these talents work for Swiss startups and scale-ups, and how many for the Swiss labs of Google, Meta, Apple, Microsoft?

That’s hard to say in exact numbers. But clearly, one fuels the other. Many former employees of corporates like Meta or Google take their expertise with them to build something themselves. The so-called flywheel—the culture of spinning off startups from successful large companies—is not yet as strongly established in Switzerland. In the USA, the status of an ex-Google or ex-Meta employee is almost a badge of honor that legitimizes the know-how to found your own startup.

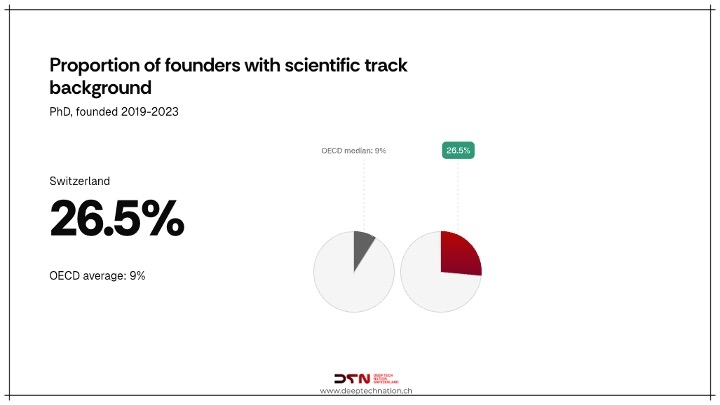

Nevertheless, we see many domestic talents in Swiss startups, and the image of working in a startup has improved significantly. What’s striking is that a large proportion of founders at ETH and EPFL are not native Swiss, but came here for their studies. This shows that risk aversion is still strongly embedded in Swiss DNA.

Reverse Brain Drain Is Possible

How big is the problem of “brain drain”? Or to put it differently: how many ETH/EPFL graduates found companies in Switzerland—and how many go to Silicon Valley or large tech corporations after 2-3 years?

There’s no concrete figure for this. But we’re observing a promising trend: the newest US policies around visas, restrictions on research freedom, or the number of international students could even trigger a reverse brain drain—at least of researchers—from the USA to Switzerland. They then import the founder mindset, which could lead to more company formations in Switzerland—brain circulation instead of brain drain. Whether someone goes to Silicon Valley also depends on where the largest market is. If the USA is a main market and a founder moves there for a while, that’s not necessarily brain drain.

This is exactly where Switzerland and Europe need to step up: we need more demand in Europe, otherwise injected growth-stage funding won’t help either. That means not just investors, but also established corporations as potential customers need to become bolder. In the USA, a pilot project can be negotiated in a few weeks; in Europe, the process often takes much longer. Time that a startup doesn’t always have.

“What’s striking is that a large proportion of founders at ETH and EPFL are not native Swiss, but came here for their studies. This shows that risk aversion is still strongly embedded in Swiss DNA.”

The “Alpine Tech Cluster”

Large Swiss corporations are potential partners and buyers. How much do these companies invest directly in Swiss deep tech startups—not just as customers, but as strategic investors? Is there untapped potential here?

Private companies account for around 68% of total R&D volume in Switzerland. Many of our startups conduct fundamental R&D that is highly relevant for corporations. R&D can be acquired through acquisitions, as we see in the biotech sector. Many corporations like Novartis, Roche, or ABB have also established Corporate Venture Capital (CVC) arms.

However, two opposing goals often collide here: corporates want to buy innovation as cheaply as possible; VCs want to make companies as valuable as possible. We need stronger engagement in pilot projects—and faster. Startups live from testing and failing; pilot projects give them credibility and capital. CVCs should invest more strongly without having acquisition as the primary end goal, because everyone benefits from a strong ecosystem.

The report names the “Alpine Tech Cluster” (Zurich–Munich–Milan–Grenoble) as one of the two leading European deep tech clusters. How concrete is this collaboration? Are there joint funds, accelerator programs, talent pipelines—or is this primarily a geographic concept?

The Alpine Tech Cluster is more than just a geographic concept. We already see accelerator programs like the HSG Start Accelerator recruiting along this axis. Many funds also invest along this axis. The talent pipeline depends heavily on scientific collaboration, which is supported by programs like Horizon Europe and Erasmus. Collaboration with the EU is central, and Switzerland should maintain and nurture these relationships.

Swiss Founders and Startups Are Known for Their Precision

In international comparison, Switzerland is considered risk-averse. Do you have concrete data or examples showing that Swiss founders act more conservatively—or that promising projects fail due to insufficient courage from investors or founders?

The high proportion of foreign late-stage investments points to risk aversion. Many founders who study in Switzerland come from abroad, and the mindset hasn’t arrived with all Swiss people yet. However, risk aversion also has advantages: Swiss founders and startups are known for being very precise. The risk-averse thinking is often reflected in pitches. Anecdotally, the American pitches the business, the Swiss the technology or product. With investors from the Anglo-Saxon world, this may create the illusion that Swiss startups are less lucrative. That’s not the case.

However, we need to be careful not to cement these stereotypes. Yes, risk aversion is still there. Among founders who are too research-focused, and among investors. But if we don’t actively work on a narrative of success stories and believe we can change this, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Our task is to show with positive examples that precision and entrepreneurship go hand in hand.

“We Don’t Have a National Deep Tech Strategy”

Germany has more population, more industry, a larger domestic market, but lags behind Switzerland. Why?

There are three main reasons for this. First: capital intensity. According to our Swiss Deep Tech Report, Switzerland allocates over 60% of venture capital to deep tech—the highest proportion worldwide. This leads to higher capital intensity. Second: ecosystem density. Despite the partly decentralized structure of our ecosystem, geographic distances are much smaller, enabling synergies between cities and ecosystems. Third: university excellence. In European comparison, ETH and EPFL are clearly in the lead.

What does Deep Tech Nation specifically demand from Swiss politics and business? Is there a national deep tech strategy, or is development primarily bottom-up driven?

Currently, development is primarily bottom-up driven. We don’t have a national deep tech strategy, although most European countries and the EU have had one for some time. We see ourselves as a connecting link in this process. Our demands:

- To institutional investors: Invest more money in VC and aim for longer investment horizons that bring higher returns in the long term (for example, as investors in vehicles like the AWI Deep Tech Fund).

- To business: Implement more and faster pilot projects with Swiss startups, and promote M&A of startups instead of only conducting in-house R&D.

- To politics: Maintain contact with the EU and ensure collaboration. Stronger public participation in growth financing, as well as investor- and startup-friendly framework conditions, for example uniform tax guidelines for employee equity participation.

Five-Year Survival Rate of 92.9%

How sustainable is the current deep tech boom? Is there historical data showing how many of the deep tech startups founded between 2010 and 2015 still exist and are successful today?

The numbers show high sustainability. The ETH Spin-off Report shows that companies founded between 1973 and 2018 have a five-year survival rate of 92.9%. The combined value of Swiss deep tech companies founded between 2010 and 2015 has continuously increased and is now bearing significant fruit. Even after the investment boom, resilience was evident: while the general funding decline after 2021 was 60%, the decline in deep tech was only 28%.

About This Article

This article was originally published in German by Technik und Wissen, Switzerland’s leading industrial technology magazine, in their December 2025 print edition and online.

Author: Eugen Albisser

Original article: Kleines Land, grosse Deep-Tech-Nation

Publication: Technik und Wissen – Print Magazine Issue 12-25

English translation published with permission. For the original German version, visit technik-und-wissen.ch.

More Content

-

On January 29, 2025, SIX Swiss Exchange and Swisscom Ventures convened Switzerland’s tech community for a frank discussion about IPOs. With BioVersys reflecting on its…

-

The Relay Node Olivier Laplace, Partner at Vi Partners, still views the world through the structural lens of a software engineer. While his days of…

-

From Relaying to Refunding If Part 1 was about the who – Olivier Laplace as the “relay node” in a vast network -Part 2 is…